Movies, unlike TV shows, don’t have episodes. They don’t

have a specific time slot they appear in every day or week. So they can’t

necessarily rely upon a returning captive audience that knows all the

parameters of their offering.

As such, the description of a movie in an EPG (Electronic

Program Guide) must inform the potential viewer fully—without divulging any

information that would diminish the viewer’s enjoyment of discovering the film

on their own.

So, a movie description in a TV listing should DESCRIBE, and

not DIVULGE.

There are a number of editorial standards that make a good

description. As usual, we’ve listed them here for you.

1. That’s a description,

not a kitchen sink.

We’ll begin by defining a description to be an accurate reflection of a film’s content regardless of extraneous info like the director, the year it came out, who stars in it, or how many awards it won.

We’ll begin by defining a description to be an accurate reflection of a film’s content regardless of extraneous info like the director, the year it came out, who stars in it, or how many awards it won.

With this editorial standard, viewers can assess a film

without considering all those other factors—which are still available to be

evaluated OUTSIDE the description. Added on as another layer of important

information, but without “tainting” the description itself.

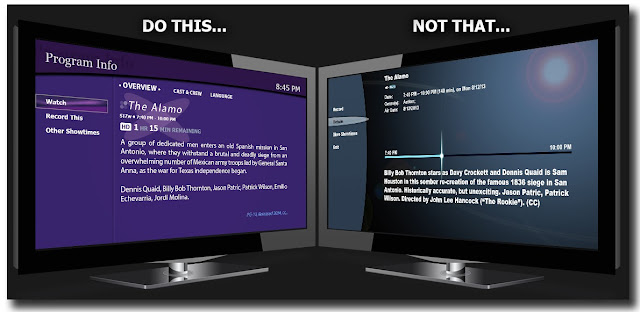

Good descriptions, as seen in our example, confine

themselves to describing just the film in an objective, positive manner. (Just click on the images view them in a larger size.)

The bad example? Well, they’ve “kitchen sinked” it. Thrown everything in there

and expected you to sift through it.

Just look at it. It’s got actor’s names, a smattering of

plot, a biased review, a non-sequitur actor’s name, and a spoiler that

references a dubiously memorable scene.

So, in the bad example, the film’s story doesn’t get just

due, and other elements are similarly watered down and mixed together so a

viewer doesn’t really know what to grasp.

Remember, a description is just that. A description. Not a

list of credits or a resume or anything else. Even in a bizarre hodgepodge.

Therefore, a description shouldn’t read like a ransom note

with every random bit of info thrown in like jumbalaya.

2. The movie can spoil

itself—you needn’t include any spoilers.

How many of us have wanted to scream when a friend or co-worker reveals the surprise plot points of a movie?

How many of us have wanted to scream when a friend or co-worker reveals the surprise plot points of a movie?

The scream doesn’t get any quieter when an Electronic

Program Guide commits this same sin. Because DESCRIBING a movie doesn’t mean

DIVULGING the important dramatic details.

Painting a picture for the viewer is great—but needs to end before

the point when a synopsis gives up plot points the viewer would naturally want

to discover on their own.

For instance, in our examples, divulging the fact that Paul

Rudd’s sisters “eventually realize his optimism might actually be a strength”

is a spoiler. It gives away the direction of the film and totally eliminates

any discovery possible on the part of the viewer. Going well beyond the general

description into an inference the viewer should probably make on their own.

And it could even be worse than that.

Revealing that Norman Bates’ mom is dead in the synopsis of

Psycho totally reveals an important plot point and destroys the illusion the

film is trying to set forth—although it is part of the story. But, as you can

see, being part of the story doesn’t automatically mean being part of the

description.

Describe, don’t divulge.

3. Leonard di Caprio

didn’t die in Titanic—Jack Dawson did.

“Leonard di Caprio and Kate Winslet are star-crossed lovers aboard a doomed cruise ship…”

“Leonard di Caprio and Kate Winslet are star-crossed lovers aboard a doomed cruise ship…”

We beg to differ. No, they are not. JACK and ROSE are the

star crossed lovers in the film. They are merely PORTRAYED by Lenny & Kate.

Thus, in the description, no mention should be made of the actors who play the characters

in the film.

After all, there’s a whole separate section for the actors

where they can be viewed in one fell swoop.

In our example, Wesley Snipes (the actor) is attributed to

being a vampire slayer. Well, he PORTRAYS a vampire slayer in the film Blade,

but the vampire slayer is actually named Blade. Not Wesley Snipes.

There’s a difference between the actor and the character he

or she portrays. You’ll also note that Kris Kristofferson’s name is listed

somewhat randomly. We’ll assume it’s the singer/songwriter/actor and not a

character named Kris Kristofferson. Another good example of why not to include

actor’s names in descriptions.

Placing actors in the description skews the information away

from the actual description of the film and again “taints” the information with

the draw—or lack thereof—brought about by the star in question. Also, choosing

to exclude the actor’s name in the description means a focused exposition of

that actor’s character. Perhaps their vocation, or aspects of their personality.

Those are unique to the film’s DESCRIPTION and not the ACTOR.

Keep the actors names where they belong. In the cast

section. The description of the film will be made all the more vivid and pertinent

if you do.

And, for the record, Leonard really didn’t die in Titanic. Trust

us. He can’t be dead. We’ve seen him since then.

4. Who asked for YOUR

opinion? Describe, don’t pontificate.

A description, as we’ve mentioned, is just that. It describes a movie fully—giving the potential viewer a robust idea of what the film is about without divulging key plot points.

A description, as we’ve mentioned, is just that. It describes a movie fully—giving the potential viewer a robust idea of what the film is about without divulging key plot points.

Certainly, no one would ever place a negative (or a

positive) subjective, biased, and non-binding OPINION of a movie in a

description, would they?

You’d be surprised.

Take, for example, this description of The Alamo.

“Historically accurate, but unexciting.”

Where to begin on the wrongness of this being in the

description?

First, this is clearly a subjective OPINION and not a

description. Second, amazingly, this opinion actually discourages a viewer from

watching the film. Lastly, the opinion doesn’t come from an immediately

qualified source, nor explain the reasoning behind the conclusion.

So, we can’t really check into proof of historical

accuracy—which is also subjective. It’s certainly not a description of the

actual film.

To sum things up, a description should only contain

information that allows a viewer to decide yes or no—NOT information that’s

already made that decision for them. That’s called a review and it’s different

than a description.

Remember The Alamo. Not the subjective review in a

description.

5. The film’s plot is

not a description—otherwise, the EPG would just show the script.

General description of action is great—that’s part of what a description is and what it should do. It should, in broad but meaningful terms, give an indication of the film’s subject matter.

General description of action is great—that’s part of what a description is and what it should do. It should, in broad but meaningful terms, give an indication of the film’s subject matter.

However, a point by point narrative of specific action is

NOT a description.

In this example, from I Still Know What You Did Last Summer,

the bad version goes on a point by point delineation of the plot—even giving

specifics of action and location of action. Right down to the karaoke session.

Too much plot tends to spoil the film for anyone who hasn’t

seen it yet. Specifically, the people searching and EPG for something new to

watch and seeing the spoiler-ridden “description.”

6. A movie description

is a specific thing—accept no imposters.

Many times, various attributes of a film are inserted into a description that do not describe the actual film presentation itself.

Many times, various attributes of a film are inserted into a description that do not describe the actual film presentation itself.

While these facts may be interesting and may even drive

viewership, unless they’re a description of the film, they’re in the wrong

place. If you’ve read the description

and know more about the actor’s background or any awards the film won than what

the film is actually about?

Then there’s a problem.

Our bad example features some bad guys—the gangsters in

Goodfellas. However, the description is even worse than bad. It has only an

inkling of description and a trivia fact serves the purpose the description was

intended for.

After reading, the viewer knows more about Martin Scorsese

and Joe Pesci than they do the movie Goodfellas.

Descriptions describe the film. The actual presentation on

the screen. Box office information, the director’s previous film, awards, and

other information might masquerade as a description, but don’t you be fooled.

No matter how many awards they list.

Because movies are also pay-per-view entities that can

generate revenue, descriptions have to accurate, complete, and specific as

possible.

The art of writing movie descriptions can have a blockbuster

impact on a viewer’s ability to make an informed choice. Let us help inform

your choice of a TV listings metadata provider by simply clicking below.

That was helpful,

ReplyDelete